Seabed Warfare: where technology meets security

Seabed Warfare: where technology meets security

Over 80% of global trade is seaborne. About two-thirds of the world’s oil and gas supply is either extracted at sea or transported by sea and up to 99% of global data flows are transmitted through undersea cables. None of this information is new but it pays to remind ourselves of these facts at a time when reliance on undersea infrastructure has never been higher and is likely only to increase.

The National Protective Security Agency (NSPA) provides the UK government’s definition of Critical National Infrastructure (CNI). While the definition applies to all infrastructure, not just maritime, terms like cables and pipelines are absent. CNI is defined by the impact of loss of its availability, integrity or delivery of essential services. The global economy and need for energy security leads us to conclude that a great deal of that seabed infrastructure is critical to the national interest.

Your infrastructure is at risk

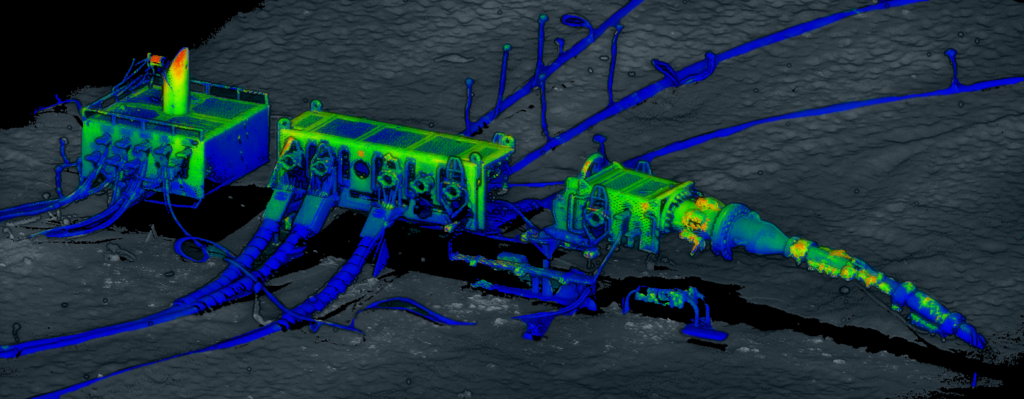

Just as the technological explosion of land and air drones is re-writing land doctrine in Ukraine, the development of highly capable remotely operated and autonomous underwater vehicles has put more of our seabed based national infrastructure at risk from our from our adversaries. While communication pipelines tend to be buried, the nodes and shallow infrastructure are vulnerable, and oil and gas infrastructure is largely exposed and detectable with rudimentary technology.

Technology options

So how do modernising navies regain the advantage and protect our critical national infrastructure? Sub-surface and Seabed Warfare is not new, nor is it a discrete domain of underwater warfare. During Forcys’ discussions with navies around the world, we see the distinctions increasingly blurred between: port and harbour defence; persistent area surveillance; mine warfare; mine countermeasures; environmental protection compliance; hydrographic survey and military data gathering; intelligence collection; anti-submarine warfare and submarine operations. The enabling factor in this is off-board systems. Off-board systems can provide more mission options on increasingly scarce platforms. Containerised solutions provide operational flexibility to switch between roles.

Navies are wise to consider the technical solutions that have been developed for the offshore energy and scientific research sectors. The offshore industries routinely deploy autonomous underwater vehicles (AUV) systems, remotely operated vehicles (ROV) systems, and towed vehicles – all capable of detailed inspections. The same technology that monitors pipeline health – from side-scan sonar to high-resolution laser scans and optical imagery – can be repurposed to identify suspicious activity. In the same way that the effectiveness of a navy is multiplied when it operates at sea (within reasonable limits it could be anywhere), the presence of credible autonomous systems provides an effective deterrent to an adversary. Exploration in deep water is leading to resident AUV and ROV systems performing surveys and maintenance between underwater re-charging and data transfer. These systems can be supported by precise positioning networks and through water communications to enable real-time monitoring, warning, and response. From a defensive perspective the presence of credible autonomous systems employed randomly in an outward surveillance mode may deter an adversary from their course of action.

Recent workshops relating to use of unmanned systems and the likelihood of our forces needing to operate in diverse and potentially unfamiliar environments to protect our nation’s interests all raise a common observation: that industry holds the bulk of the knowledge of what infrastructure lies on the seabed, what that infrastructure is carrying (to allow an assessment of how important it is) and the environmental conditions of the area. Recognising that offshore companies have paid large sums to obtain this data, some of which could be useful to a competitor, there is no appetite to freely share such information. A frequent comment by naval officers is that “you would not believe just how much infrastructure there was on the seabed”. This begs the question of whether navies are ready to operate safely and effectively within such an unfamiliar and poorly understood environment.

Partnerships

So, how can companies be encouraged to release the data they hold? Abstracted to a problem of source protection, security and sharing the answer is, optimistically, yes: anything is possible. But realistically, to overcome significant challenges including multinational ownership, individual company vulnerabilities and cost of implementation this must be government led. At Forcys we are encouraged by initiatives like NATO Digital Ocean and the establishment of the CNI Hub at NATO Maritime Command. At a national level in the UK where I am based, there is surely a role for the NSPA or UK Hydrographic Office in managing a limited access database of seabed infrastructure within the UKs Exclusive Economic Zone for use by UK Defence if required. Perhaps the most compelling reason to support data sharing is the benefits that the improved protection will bring. Time will tell.

Ultimately, the short-term future of seabed warfare does not lie exclusively in expensive new unproven technologies, but in smarter ways to use the tools we already possess alongside breakthrough capabilities. By working together, we can ensure the safety of our underwater lifelines, keeping the lights on and the world connected. At Forcys, we understand both the threat and the technology. We want to be where technology, experience and innovation meets security.

Justin Hains MBE left the Royal Navy in 2020. Among other professional qualifications, he completed the Advanced Mine Warfare Course and the Amphibious Operations Planning Course during a career as a Mine Warfare Clearance Diving Officer and Principal Warfare Officer (Underwater).

More from The Watch

How could industry and defense work collectively to enhance the security and protection of critical national undersea infrastructure?

How could industry and naval forces work collectively to enhance the security and protection of critical national undersea infrastructure?

Share On